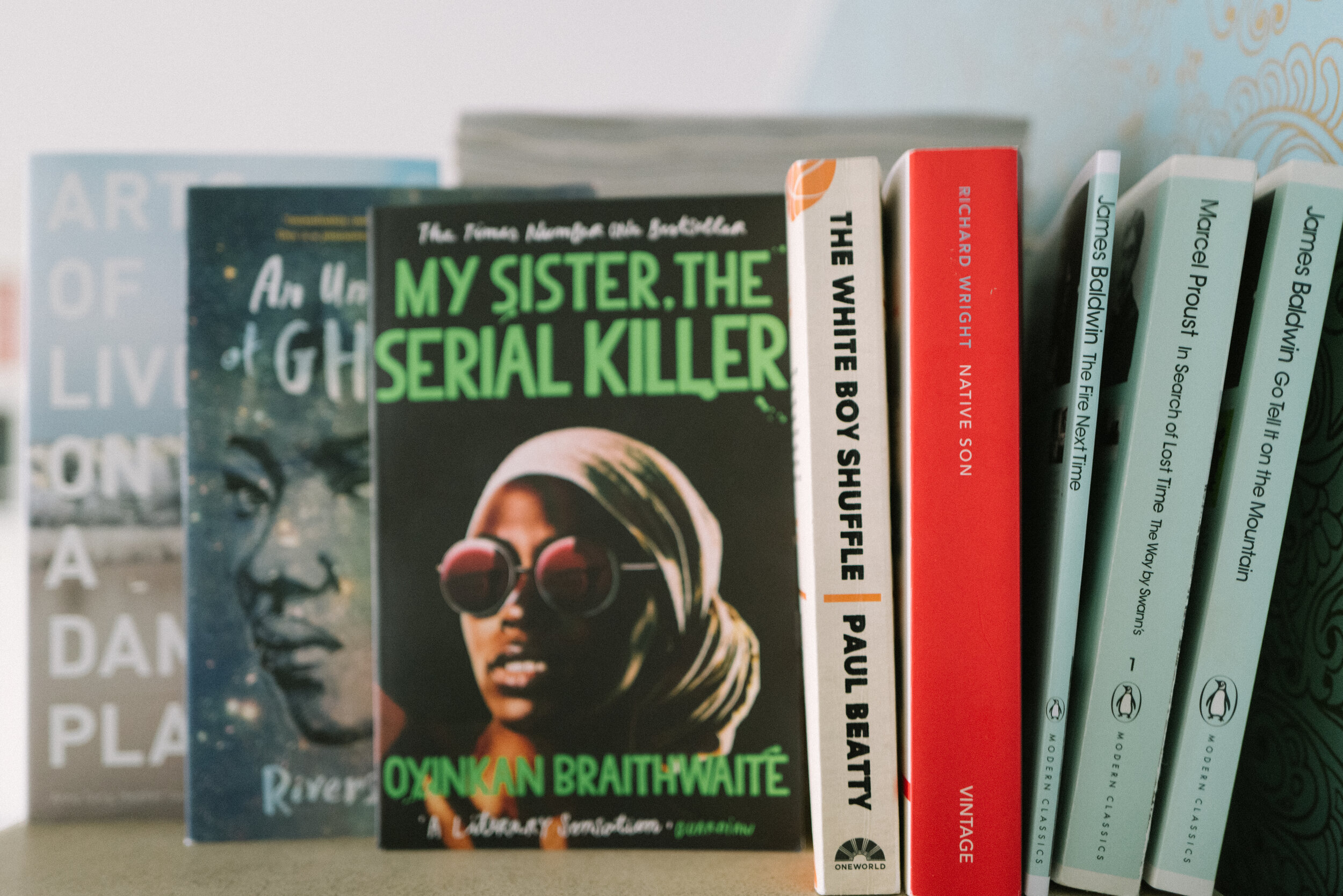

June 2020 Books

With everything going on in the world at the minute, I struggled to get as much reading done as I wanted to this month, but what I did read was mostly of a very high quality, so swings and roundabouts, eh? I also wanted to champion Black writers more than usual this month in the wake of the global Black Lives Matter protests. Granted, these authors hardly need me to rave about their work but I just wanted to take the time also for myself to focus and delve into their writing. If you want to hear me talk about that a little more, including what it means to read diversely, and to be wary of and responsible for your white privilege whilst reading authors of colour, you can watch my June books video here.

This was also the month I decided to stop giving books ratings. As I mentioned in this post towards the beginning of the year, I’ve been struggling for a little while with rating books; sometimes a book is obviously important or striking in its style, but it simply isn’t enjoyable or my cup of tea. Sometimes a book lingers with you longer than you thought it would, or a book you thought was mind-blowing initially becomes all too easily forgotten a few weeks later. Books are complex, and I want to let them stand in all their complexity by simply expressing how I feel about them in my reviews. This is a bit hypocritical of me, I know, because I do find the aggregated rating to be quite a useful tool on Goodreads; if it’s higher than four I’m likely to pay closer attention to the book and have a look at the reviews; if most of the reviews are hovering around three stars I’m more wary - after all, I haven’t got time to read everything! So yes, I know it’ll probably be a little annoying that you won’t be able to tell at a glance how I (sort of) felt about a book, but I hope that I can allow books to speak for themselves a little more, and stop giving myself a headache trying to pick between three and four stars at the same time.

Highs

Go Tell It on the Mountain by James Baldwin

This novel seemed like a good fictional companion piece to The Fire Next Time, which sort of picks up where this leaves off and provides some background on Baldwin’s life before the writing of those infamous essays. Because indeed, this book is semi-autobiographical; it follows young John Grimes growing up in Harlem in the 1930s. John is fourteen, and thus struggling with all the intense emotion of a boy growing up. This is further compounded by the abusive behaviour of his minister father, and where his father represents the Church, John finds himself grappling with religion also. He is also experiencing some confusion regarding his sexuality. In the following chapters, we are introduced to his aunt’s, father’s and mother’s perspectives and histories that have brought John and their family to Harlem. Within these histories lies trauma and issues of racial and gendered oppression.

One of the main functions of this novel is to scrutinise the role of the Church in the oppression and repression of African-Americans at the time, and that is a theme that is picked up in The Fire Next Time. Towards the end of the novel, John has a spiritual awakening of sorts, and what I love about Baldwin’s work in this book is his acknowledgement of the nuance of human experience. There is real spirituality to this moment and to the language, but at the same time it seems to resolve very little in the long-term; John is still facing issues with his father, with his sexuality and, as we will find in the below book, probably with the Church eventually, too. Baldwin’s language is deeply emotive and completely hypnotising, and though he certainly has a lot to say in this novel regarding religion, race, class, gender and sexuality, he manages to do so in such a way as to explore all the shades of grey that exist in the intersection of these things with the powerful feeling of human life. I don’t know what I was expecting with Baldwin, but I was utterly surprised by the sheer power of emotion in his work, and I found reading him to be a deeply moving experience at quite a difficult point in life. I can’t wait to read more, Giovanni’s Room is definitely next on my list.

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin

Then we have this short book which consists of two essays, one a letter to his nephew on the hundredth anniversary of Emancipation, and the other a more meandering look at various ideas, particularly religion. In the former essay, Baldwin offers advice to his nephew in how to navigate a world that discriminates against him based on his race, and explains to him a little what has happened over those hundred years since Emancipation. The latter essay details Baldwin’s experience as a teenage preacher after his spiritual awakening, his difficulties with the Church and his time spent with Elijah Muhammad. Muhammad was the leader of Nation of Islam, and Baldwin describes in this essay how he finds some of the work they were doing to be persuasive, and other parts less so, providing a nuanced look at what they were offering their African-American followers at the time.

There’s so much in this short volume that is still devastatingly relevant today, and some very quotable sections that prove Baldwin’s power to succinctly describe the complex entanglement of racism in America. No doubt some of it is a little out of date, and it’s worth reading contemporary accounts and essays too (I’m currently reading The Fire This Time edited by Jesmyn Ward!), but I think this is an important read from one of the great Black writers. He still brings so much powerful feeling into these essays, and I can see why they are still so popular today.

Native Son by Richard Wright

I found out about this book from the wonderful Hena, or Bookish Babe, as she listed it in her first video as one of her all-time favourites. Wright was writing a little before Baldwin’s time, and this book was published in 1940. As I say in my video if you have the same copy as I do with an introduction by Caryl Phillips, it’s well worth reading it to provide a little context for this book. In it, Wright was trying to show white readers their own responsibility in perpetuating structural racism and racial oppression even in insidious ways, particularly through the operation of capitalism.

It is about a young man named Bigger Thomas, who is living in poverty on the south side of Chicago and through this profound sense of fear and hatred he has of the world, he begins to commit murders and to unintentionally play into all the stereotypes of black masculinity of the time. Though he initially works for a white family that seem to be kind and sympathetic to the cause of African-Americans, he later discovers that they are the family that owns his apartment building, charging Black renters exorbitant rates compared to their white counterparts, as well as practically forcibly segregating them to certain parts of the city. Toward the end of the book, Bigger’s lawyer gives a famous speech whereby he asks that the jury need not see Bigger as a victim (and indeed, he does some pretty heinous things in this book), but that we do need to acknowledge as a society how structural racism leads to crimes and lives like Bigger’s, and that in addressing those structural issues, one might avoid them in the future. Wright’s assertion is obviously backed up these days by plenty of evidence that crime can be reduced not by investing in more punitive measures (police and the criminal justice system), but by investing in communities.

Baldwin himself took issue with this book for portraying Bigger as a stereotype and for having too overt a political agenda instead of a more artistic eye. Whilst I can see where Baldwin might have been getting at at the time - with fewer books by Black writers and this being a runaway success with Black and white readers, it could be seen as doing more harm than good, especially if it’s read wrong (we’ll get to that down below). But like many readers since, I think there is certainly a case to be made for this book now. The narrative tension is incredible; I read very few books which pull you along quite like this one and have your heart racing, especially books from this period. In that sense I certainly don’t think this book is all political tract no art; to create such a fast-paced thriller feel is difficult in and of itself! I also thought that Wright was actually exploring quite a lot of nuance in the way Bigger felt and acted, and his inability to get his thoughts together or interrogate his own motivations. There is also so much going on here about the weaponisation of white femininity as well as the racist blunders of white people who seem to want to help Bigger but patronise or victimise him all over again. It is a deeply affecting book, particularly as it gathers towards its conclusion, and I certainly won’t forget it anytime soon. I definitely want to read Wright’s memoir Black Boy next.

The White Boy Shuffle by Paul Beatty

So this is the book that broke me and my ability to rate books! It’s deeply complex and layered and I definitely do it an injustice every time I try to talk about it but we’ll give it a go. Forgive me, Paul Beatty.

It’s about a Black teenager called Gunnar Kaufman (what a name!) who is living in suburban Santa Monica (with a ‘surf bum’ sort of lifestyle) when his mother thinks he’s too far removed from Black culture and his racial identity, and so moves the family to urban West Los Angeles. Obviously this alone sets up certain assumptions and ideas about Black identity in itself and this is something Beatty is definitely aware of and is playing up. Gunnar then must readjust himself to his new life and the tension between who he was and who he becomes is the driving force behind much of this book.

Beatty’s style is completely unique; he is often described as a satirist even though he has repeatedly denied in interviews that he considers himself one. Certainly there is a fair amount of satire and humour running through this book, but there is also something decidedly more dazzling and heartwrenching going on here, too. He holds nothing sacred and cuts through everybody’s bullshit, delineating Gunnar’s family background, his experience adjusting to his new life, and the ultimately absurd and heartbreaking ending in quick, witty, constantly dancing prose. Woven into every page are (sometimes obscure) historical or cultural references, and I certainly think knowledge of elements of Black culture and Black history are useful before approaching this book. Obviously I’m white and I managed okay, though I did keep Google handy for those parts I was less sure of and thought were probably particularly important (I doubt you’ll get them all on the first read!) Beatty manages to show the absurdity of racial politics, looking through the issues with a kaleidoscopic viewpoint that twists and turns concepts into new, unrecognisable forms. (Just a big TW on this book is that Beatty uses suicide as a trope from the outset; this obviously won’t sit right with everyone - though as I said Beatty holds nothing sacred - and will certainly affect some readers’ experience with this book)

If you are a non-Black reader, I suggest you approach this book with care, and self-monitor what message you are taking away from it. I don’t think all the jokes are for us, and I don’t think we should be finding absolutely everything funny. I worried at times that white or non-Black readers might use parts of the book as license to be derisive towards certain parts of Black culture, or even to be outright racist, but I think this is a dangerous spot to put Black authors in, policing what they can and can’t write on the basis that a white reader might take it wrong. Instead, we need to make room for them to write in their fullest scope, and to be controversial and daring in ways that we often allow white writers to be. So whilst I wouldn’t recommend this book to anyone who is totally new to Black writing or to anti-racism work and might find it more difficult to self-monitor some of their reactions, I think Beatty’s work is absolutely worth reading if you want something that will challenge you and provide a totally unique perspective on the world. I’ve since bought both of his novels that I didn’t already have and can’t wait to read more.

In Search of Lost Time: The Way By Swann’s by Marcel Proust

What can I really add to the conversation about Proust? After finishing Ducks, Newburyport I decided to start In Search of Lost Time as my next long and challenging read, this month’s book being the first volume. If you don’t know, it’s a canonical Modernist work originally written in French, and it follows a nameless narrator growing up in Aristocratic France at the end of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. This first volume covers some of the events and feelings of his childhood, but Proust’s main object across this expansive work is to explore ideas of memory and reality. He is interested - particularly in this volume - with involuntary memory and the way that sensory experiences can take you back to a particular moment in time. He also looks at the disjunct between thought and reality, whether that be in memory, in everyday life or in anticipation of something. And finally, he also seems to be trying to pin down the reality of the mind, the liminal space where subconscious and conscious interact. It’s quite wonderful and I can see where it has had so much influence over the past hundred years or so since its publication. It’s also not as experimental in style as I was expecting. Certainly, it’s difficult to read in that it’s lengthy and wordy so you’re going to need a hefty dose of concentration and some peace and quiet (he’s likely to go on for pages about something small), and much of the sentence construction is purposefully obscure (to more accurately depict the workings of memory), but it is recognisably a novel with a storyline and for that, I was very appreciative.

Everything in between

My Sister, the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite

This is a fun, speedy thriller about a pair of sisters living in Nigeria, one of whom is a serial killer. She is beautiful and desirable and she (literally) gets away with murder, whilst her less attractive older sister is forced to come and help with clean up. Braithwaite writes in cool, slick prose and short, cinematic chapters so this is one of those novels that can be consumed whole.

I liked this book for its reversal of some of those thriller tropes where the womxn victim always ends up murdered or violated. By making the woman the perpetrator, Braithwaite is writing back at all those stories. Serial killer Ayoola subverts those men who seek to possess or fetishise her. This is not a deep, meaningful read, but I appreciated what Braithwaite was doing with this novel and I would recommend it if you’re in the mood for something quick to read that might get you back into the swing of things.

Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet ed. by Anna Tsing, Niels Bubandt, Heather Swanson and Elaine Gan

This book consists of lots of essays by a huge range of writers from a huge range of disciplines over the humanities and sciences looking at ‘our damaged planet’ and what we might do to save it. I wanted to love this because my beloved Barad and Ursula Le Guin wrote pieces for this, but in the end I found the essays to be too short and quite random (focusing on a huge selection of people’s sometimes idiosyncratic research interests). I wanted something a little more substantial and to provide me with more ways of thinking and being in the world than it did. If you watched my video though, you’ll know that this has got to be one of the most beautiful nonfiction books I own!

End of Policing by Alex S. Vitale

I wanted to learn a little more about some of the alternatives to policing so I turned to this book. In each chapter Vitale looks at social issues that the police tackle that they probably simply shouldn’t be on the frontlines of, from the War on Drugs (which has been proven ineffective time and again) to sex work, homelessness and mental health problems amongst other things. Instead, Vitale advocates for providing secure long-term housing and permanent jobs, as well as social services in underfunded communities to provide everything from proper mental health care, to youth services and education. He shows how police forces came into being; in the UK they were mostly used to suppress social movements whilst in the US it was on more overt racialised lines (though immigration and the perceived threat to safety that it poses means that race has played a part in both police forces) through catching slaves, and in general quelling riots and protecting property. Though police forces now show a concern with general crime, he shows that this often “makes their social control function more palatable”.

This book is good if you want lots of facts, figures and studies. It’s not about theorisation and it’s not supposed to be gripping or fantastic writing, it’s there to educate and it does a fairly good job of doing so. I imagine for many people this book is not radical or imaginative enough, as many of his ‘alternatives’ look like the reforms that he tries to reject (reform only seeks to legitimise the police and legitimise its role in, say, policing homelessness). However, I do think it is quite a pragmatic and useful book, and I will be reading more around the subject.

Lows

An Unkindness of Ghosts by Rivers Solomon

Instead of placing this month’s ‘Low’ up above I wanted to hide it a little bit because I do feel bad about how much I didn’t like this novel, especially because I can see what Solomon was trying to do with it. As this was their debut and they are fast becoming a much-beloved author of colour within science fiction, I’m loath to burst anyone’s balloon that enjoyed this book. However, I just couldn’t get on with it no matter how hard I tried.

It’s about Aster, an intersex character (whose pronouns are she/her) who lives aboard a spaceship modelled after the antebellum South. She lives on the lower decks with her fellow dark-skinned womxn and non-binary people, and she must perform manual labour and try to survive under the abusive eyes of the Guards. I had lots of problems with this book, the first being that it felt quite messy. The plot was a bit thin on the ground, and as a result, there were lots of needless scenes. The science, mechanics and visualisation of the ship were also a little lacking; I feel like Solomon might have done better actually explaining less in this regard. Whilst there were hints of beauty in the language, a lot of it felt overwrought without the substance in the plot to back it up. So in general terms, I found it to be difficult to get through. Furthermore, I wanted more from Solomon as to the background of the cultures on the ship. For example, each of the different decks at the lower levels has a different approach to gender; whilst I appreciate all the representation that Solomon fits into this novel (and I’m so pleased that so many readers have found representation for themselves in their words that they haven’t found elsewhere), I want to know what is it about these different cultures and their lives pre-Matilda that caused this, and what it really means to the people living on those decks; is it a hindrance that adds to their oppression? Or a way to break out of moulds and be creative? Is it both? There was a lot that I thought might have been explored in greater detail. So, all in all, I didn’t love this book, and couldn’t recommend it, but I am interested to see how Solomon has developed as a writer and if their next books are very different.

So that’s it for this month! I hope you enjoyed.