March and April 2023 Books

As you can see, I read a shedload of books in March and April. Admittedly, this is probably time I should’ve spent doing other things, but I have no regrets because it was hit after hit after hit for me these past couple months. Some seriously good books came my way, and very few bad ones (thank you again, power of the DNF). Because there were so many, I’m not going to go into heaps of detail about every single book here lest this be the longest post ever, but I will be talking about the best of the best extensively I’m sure over the next few months.

The Best of the Best

White Cat, Black Dog by Kelly Link

I am a bit allergic to fairy tales in contemporary literature. Too often they just don’t work for me, with the author failing to translate the real significance and power of the originals into modern settings or concerns. Often, they’re used in a half-hearted stab at some ‘symbolism’, which is really just a bit of literary laziness (looking at you Mischief Acts which was a bit of a meh attempt at an eco-fairy tale crossover). But Link’s reimaginations of classic fairy tales (though many you won’t recognise off the top of your head) are just perfect. And this is why: she clearly deeply understands the structure and purpose of the fairy tale, meaning she’s able to transpose this into a selection of contemporary – and sometimes even futuristic – stories. Often they are almost unrecognisably different from their source material, and that’s exactly why they work. Before I read these, it hadn’t outwardly occurred to me how weird most fairy tales are; the sharp turns in the narratives, the illogic. Link’s stories will undoubtedly make you reflect on the fairy tales you grew up with and also delight you in their own special weirdness. They are neither too on the nose, nor are they too wishy-washy. A particular favourite was the story where a college student struggling with his dissertation ends up house-sitting for death. I highly recommend these if you’re looking for something fun and weird to read, which will also have you marvelling at how easy it all seems to come to Link.

Gilead by Marilynne Robinson

I’ve been wanting to read this novel for years, since I read Housekeeping long, long ago in my third year of university. Which is another excellent novel, by the way. But boy, did this one come at just the right time. I read this just as the trees started to blossom, and the sun started to peek out from behind the endless winter clouds, and it just sang to me. It’s written from the perspective of an old preacher living in small-town Iowa sometime in the middle of the twentieth century. He finds himself an unusually old father and feels the failings of his body and that his end might be near, so he pens this long letter to his son to give him an idea of who his father was. It’s a slow, meandering novel that reflects on the beauty of life and its fleeting nature, the difficulties and trauma that are passed down between generations, the love we hold for those around us, and of course, faith. Although I’m not always a fan of very religious novels, this one was perfectly done. John Ames’ overwhelming love for life and people shines so that many could easily relate to it, whether you’re Christian or not.

Even though this novel sometimes feels like it’s going nowhere, to me it was very masterfully plotted. Some of the images of his earlier life come back to him repeatedly, gently iterating and working themselves through in the narrative. The world Robinson builds is so believable and complete. I also enjoyed both the earlier sections where Ames reflects on the differences between his father and grandfather (both also preachers), and the later sections where he wrestles with his seemingly instinctive dislike of the boy named after him by his closest friend, the surrogate son before he had his own. I do think this book probably isn’t for every reader (and the others in our buddy read for this weren’t quite so keen), but if you do like quiet, reflective novels, I think you’ll probably really enjoy this one. I can’t wait to read the others in the series, which follow the perspectives of other characters in Ames’ town.

Paradise by Toni Morrison

This is just a perfect book. Absolutely no notes. Incredible, incredible storytelling.

Where to start? It’s about an all-black town called Ruby, on the edge of which stands an ex-‘convent’ (that was not really a convent at all) where down-and-out women find themselves a kind of refuge. Their presence alone seems to offend some of the townspeople, and a group of men decide to launch a brutal attack on the convent women early one summer morning. This is where we begin the story, but it ranges far and wide over the course of its pages.

This is one of Morrison’s longer novels, and there’s no doubt that it requires some serious reading to get to grips with it. It’s her take on the ‘big cast of characters in a small American town’ novel, so you have to closely follow the names and links between them to get a good idea of her intricate plotting here. And of course, this is Morrison, so the sentences themselves are at times practically cryptic in their lyricism. I’d really recommend paying quite close attention to this book, so set aside some time for it. I was quite glad I noted down things that make no sense early on because often these were my little puzzle pieces to put the whole together later. I was also thankful that I pushed to read it quickly because again it helped me keep the threads of the plot together.

If this sounds intense, trust me it is so rewarding. The immediacy of the characters, the depiction of the town of Ruby and its long history, the way you move through the story as a reader; it is an absolute masterclass in novel writing. I can’t even comment too much further because you have to read it to believe it. It’s my favourite Morrison reading experience so far, and I can’t wait to continue with the rest of her work this year.

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer

This was another stellar book, absolutely perfect. I listened to this, and I highly recommend this as an audiobook, because the author herself reads it. You can feel her love for what she is writing about in her speech, and it is a spellbinding experience.

Kimmerer is an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, and she is also a professor of botany and biology. In this book, she brings together her indigenous knowledge with her scientific knowledge, each enhancing and reflecting on the other. She also writes from a deeply personal perspective, with beautifully written sections of memoir included, also. This blend is so artfully done (Kimmerer admits she was between a poetry and biology degree), and really epitomises so much of how I feel about the world. There is no objectivity in the human perspective, and to adopt a purely ‘scientific’ viewpoint is practically nonsense, you only need think of how patriarchal the world of science is. And yet, of course, science can also tell us many interesting and important things about the world. It is amazing how many of these things, though, were known to some degree by indigenous communities who were displaced (to put it lightly) from their homelands, through a tradition of close observation of the natural world and communion with it. This is a truly interdisciplinary book, which acknowledges the importance of knowing about the writer, the storytelling aspect of good science, and the power of learning from indigenous communities and reconnecting with the place we live.

This book changed my perspective on many things, and also gave me a really clear idea of what I appreciate in my nonfiction, which is a deep sense of how permeable the boundary between fiction and nonfiction really is. I think this is why I have always gravitated toward fiction, because on the whole fiction writers are not trying to tell me anything without first acknowledging their own role as storytellers (and there are plenty of true things to discover from fiction). When you read nonfiction, that is a story, too. A true story, perhaps, but the way the information is presented is very intentional, and usually points you in a particular direction. When an author tries to hide that aspect of writing, I become wary, but when an author actually acknowledges this and works with it, I adore it. And of course, when I read I’m also looking for a writer that really enjoys the act of writing itself, rather than just using it as a medium to dispense information; I am a literature student at heart after all. I understand that is just a selection of preferences on my part, and that not everyone will feel that way about nonfiction and the books they read, but this book really showed me what sets a work of nonfiction apart for me. Robert Macfarlane’s Underland had a similar relationship to the world of the literary, and again, I loved it. Interestingly, though, I did not like and even DNF’d Macfarlane’s book, The Old Ways recently for being too wishy-washy and literary, when what I wanted was something more concrete. So, there is definitely a balance to be struck. Kimmerer manages it perfectly. And even better, now I know what to look for when I go to read nonfiction.

David Copperfield by Charles Dickens

This was a re-read for me in preparation for Demon Copperhead… which I of course ended up DNFing. But I enjoyed listening to it this time around! This is one of Dickens’ best, no doubt about it. So funny, so heart-breaking. The version I listened to read by Martin Jarvis was fantastic and I really recommend it (but it is about a million years long).

The Great

Biography of X by Catherine Lacey

If you’re a fan of Pew, you may find yourself surprised by this novel, which is in many ways completely different. It’s a few hundred pages long, and in great detail, it describes another United States, one where the North, West and South territories split in the aftermath of World War II. The first became a socialist haven (though not without its own problems), and the latter a fascist theocracy surrounded by a tall wall. This provides the background to a story of an artist and her wife; the artist, X, was a difficult and uncompromising person, often cruel to those who loved her for the sake of her art. She has recently died, and so her journalist wife decides to embark on a biography of her, to try and put right some of the misconceptions about her and her work.

Despite the differences, Pew and Biography of X still share a lot of Lacey’s author DNA once you scratch the surface. Again, we have a character that feels uncomfortable with their identity, though this time X takes many forms over the course of the novel, trying on different lives countless times. And again, Lacey seems to be wrestling with her conflicted feelings about the American South here, having grown up in Mississippi. You’d be forgiven for thinking that the depiction of the South would be pretty stereotypical and remorseless based on the above, but once again due to her familiarity with it, she manages to add some nuance in there, just like with Pew’s more redemptive Southern characters. And of course, the story of X is in many ways the story of this North/South divide, especially as she managed to escape the Southern Territory’s walls as a young adult, leaving behind a life governed by religion, to lead a life governed by art.

So what did I make of it all? I should mention that generally, I don’t particularly get on with ‘art’ books. I don’t know much about art, and they sometimes make me feel alienated from the subject matter. But I very easily immersed myself in this novel, and consumed it in a few days, always intrigued by what was around the corner. It helps that C. M. Lucca, X’s wife, is somewhat at a remove from the art world, and thus she provides us with an outsider’s perspective. And of course, I really liked the alternative US setting, which drew me right in as a speculative fiction fan. In many ways, I wished there had been more of it, but I understand that wasn’t Lacey’s focus here. I think there are a lot of layers at work here, a lot of great worldbuilding, and some clever reimaginings of US history. I did think it was somewhat baggy in parts; a touch repetitive here, a bit didactic there. Lacey has said that she wrote this book over many years and I think you can tell. The depth of the research is evident, but then sometimes you can feel snaggy areas that never quite got subsumed into the streamlined final product. Overall, though, this is a really interesting novel and I will be following Lacey closely in the future as I think her career is shaping up to be really promising.

Ten Planets by Yuri Herrera

This is a strange little collection of bitesize stories which I think will appeal to all fans of the weird. One story features a gut bacterium that becomes conscious through exposure to LSD. Yes, really. Another, a detective who garners all his information about his cases from the look of people’s noses. Yet another, about a man who collects monster art. Some of the stories seem interconnected, and there are a few interesting overarching themes that help tie them together into a complete whole. You can race through these in one sitting, but I think they would bear re-reading for their subtle complexity. I will definitely be reading more Yuri Herrera in the future.

Assassin of Reality by Marina and Sergey Dyachenko trans. by Julia Meitov Hersey

The follow-up to Vita Nostra! I really liked this novel a lot, it answered just enough of the questions I had from the first book, while still maintaining an air of complexity and mystery. The first fifty pages it took me a little while to get back into the Dyachenko’s style, which can be a little awkward at times, but the ideas. The ideas are unmatched. I can’t say too much more because you really have to have read Vita Nostra to even have a starting point to talk about this one, but I’m really looking forward to the final instalment. And if you haven’t read the first novel, you must!

Close Range by Annie Proulx

This was a fantastic collection of stories set in Wyoming featuring a hard-boiled selection of characters living difficult and unforgiving lives. The most famous story is, of course, Brokeback Mountain, but there were some more real standouts here, including The Half-Skinned Steer and Job History. I found Proulx’s prose at times a bit tricky to parse, mostly because of its real immersion in the local character of Wyoming language, and the technical ranching terms used, so it required a bit more concentration of me than I was able to provide sometimes. There is an innate lyricism to her language despite her gritty subject matter that reminded me of Denis Johnson, though his is perhaps a touch more distilled. If you like your tough twentieth-century American literature though, you’ll like this. And overall, I’m really looking forward to reading more Proulx.

Guapa by Saleem Haddad

This was Haddad’s debut and I found it to be a real success. It follows Rasa, a gay man living in an unnamed Arab country whose grandmother has just last night found him in bed with his lover, Taymour. We follow him over the course of 24 hours, as he worries about the ruptures in his relationships with both his grandmother and his lover, as well as the disappearance of his friend who may have been arrested. He works as a translator by day, and often attends an underground gay bar called Guapa by night, where said friend Maj works as a drag queen. Over the course of the book’s pages, we learn more about Rasa, and his difficulty reconciling his Arab and queer identities, especially after a stint studying in the US. There is a frank openness to this novel, a generosity, fluidity and immediacy to its language that makes it an impressive debut and really drew me into Rasa’s world. Alongside his double life, his complex relationship with his grandmother, and his desperation to be reunited with Taymour, he also describes the efforts of the young people of his country to make positive change, often endangering their very lives. So you can see, there are a lot of dynamics and themes at work here, and Haddad manages them well. I was slightly less convinced by the direction of the plot at the very end of the novel, but overall, I was really impressed, and I’m interested to see what he writes next.

Finch by Jeff VanderMeer

Back to Ambergris once more! This was a fitting end to the series, and I enjoyed it a lot. I especially found it more successful for me than Shriek, which dragged in parts. This is VanderMeer in his detective novel mode (though beware, crime fiction fans, because this will not operate in the way you might expect). We follow Finch, a detective investigating a bizarre double murder. But as he unravels the threads of the case, he realises its implications are far wider than he could have suspected. Because really this novel is about Ambergris itself more than anything else, and what’s happening to this strange and beguiling city. I won’t go into too much detail, but I recommend reading the Ambergris novels in order, because there is a real progression as to the fate of the city, and you’ll miss things if you haven’t read them all. Finch is developed just enough for us to enjoy his narration, but I think you’re really reading this for the overarching story, and it comes to a sufficiently weird and satisfying end.

All Your Children, Scattered by Beata Umubyeyi Mairesse, trans. by Alison Anderson

I read this short novel over a long period of time, so I don’t know that I have the most solid grip on it, but this was another debut that I was impressed with. Translated from the French, it depicts a family coming to terms with the trauma of the Rwandan genocide, and is told from the points of view of Immaculata, her daughter Blanche, and Blanche’s son, Stokely. Mairesse deftly manages the theme of inherited trauma and the revelations of the plot that unfold over the course of its pages. There is a lyricism here that could easily tip over into the ‘all style, no substance’ mode that seems to characterise so much contemporary literature, but it stops just short of this. Instead, the language enhances the effect of the novel (as it should!) This is obviously a book about some deeply traumatic events, but I think Mairesse manages to write about it in such a way that it doesn’t just become trauma porn, but instead something meaningful about a family, and a nation, coming to terms with its difficult past, and the scars that are left behind.

When We Were Orphans by Kazuo Ishiguro

One of our more polarising book club picks, When We Were Orphans was a re-read for me, but it has been so long since I first read it that it felt new in many ways. Whilst I wouldn’t say this is my favourite Ishiguro, and it is flawed in a few ways, I still really enjoyed it and enjoyed discussing it. I also think there are many interesting elements within its pages that make it worth reading, even if it doesn’t totally work for you.

It's narrated by Christopher, a young man who grew up in Shanghai to British parents, but when they both disappeared under suspicious circumstances he was taken back to England, a place that is purportedly home, but doesn’t feel like it. He becomes a famous detective and eventually decides to try and solve the case of his parents’ disappearance. But again, crime fiction lovers, this book is not going to follow the usual path of the detective novel. Because Christopher is about as unreliable as unreliable narrators get, and whilst the first half of the novel proceeds (almost) normally, the second tips into the surreal. There are so many sticky patches in the novel which will have you wondering what is going on, or what Ishiguro is doing, and often I couldn’t decide whether they were part of the novel’s failings, or whether they were actually part of its mastery, intentionally subverting everything you think you know about narrative. I think Ishiguro is such an interesting author who often writes more strangely than people think, especially outside of his best-known novels, and I’m really looking forward to reading the rest of his back catalogue, not least because his novels also speak to one another in really interesting ways. If you’re ready for a strange and mystifying journey, this one might just be for you.

Foster by Claire Keegan

Another great little story from Claire Keegan. A heart-warming but also heart-breaking account of a young girl sent to stay with a couple who have recently lost their own child. In her own family, she experiences a fair bit of neglect on account of the number of siblings she has and her parents’ focus on mere survival, and so when she encounters the affection and warmth of the Kinsellas, she flourishes. It seeks to show how even the smallest of acts can have such a huge effect on another person, especially a child. My one caveat; I listened to this one and the narrator was not so great, so I really recommend reading it.

The Good

All the Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy

I’ve added this one in here even though I technically finished it in May because I thought otherwise I’ll just forget everything! I ended up with mixed feelings on this one, though there’s no doubt there’s some good in it. It’s about John Grady, a teenage boy who is left somewhat at a loose end when his beloved family ranch is sold by his wayward mother in the aftermath of his grandfather’s death. As the future he thought he would have is taken abruptly away from him, he decides to ride down to Mexico with a friend. Of course, there’s some awkward exoticism of Mexico as a place to come of age, and some colonial overtones here which are impossible to ignore, though relatively unsurprising given McCarthy’s age and the fact this one was released in the early 90s.

So. I love McCarthy’s stripped-back style, but it doesn’t appeal to everyone. For me, there were some paragraphs in here that just took my breath away. Despite the overt masculinity of his language, I often find it really lends itself to a deep tenderness too, which I like. But this novel lost me a few times, and I didn’t feel the urge to pick it up. It didn’t have the momentum that it really needed. There were some excellent sections and others which read like a schoolboy shootout fantasy. Overall then, it was a mixed bag. I’m going to continue with the Border Trilogy, of which this was the first, to see if there is more merit in the overarching storyline. But it was nowhere near as good as The Road for me.

Ascension by Nicholas Binge

This was a solid science fiction novel about a mountain that appears out of nowhere in the middle of the sea. One expedition has already gone up to investigate, and of those who returned, they’ve come back very weird (hello, Annihilation vibes). Our protagonist is a physicist who is recruited onto the second expedition, and he almost immediately begins to observe some very odd things. I liked that this novel was quite pacey, we don’t spend too much time getting to the actual mountain itself. The character writing was good, and the concept was interesting and well-executed. But because I read so much experimental weird literature, it perhaps didn’t quite meet the heights I was expecting, especially once you get to the reveal of what is actually happening here about two-thirds of the way in. I suppose there is a final reveal too, but it still wasn’t overly satisfying. In general, though, there are some great ideas in here and I’d be interested to see what Binge writes next.

Stay With Me by Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀

This was another book club pick, and again it split the crowd a little bit. It’s about Yejide, a woman struggling with infertility to the extent that her mother-in-law forces her husband to take a second wife to continue the family line. This novel had some plot twists which sometimes really worked and at other times felt a little awkward. I also feel the blurb slightly overstates the role of the historical background in the novel, set as it is in 1980s Nigeria. Certainly, it is there, but I wanted a bit more of it, rather than the closer adherence to the family dynamics. I also thought it touched on motherhood as a theme, but perhaps didn’t go quite as deep into it as I like in my novels. But in general, it was a decent read.

The Meh

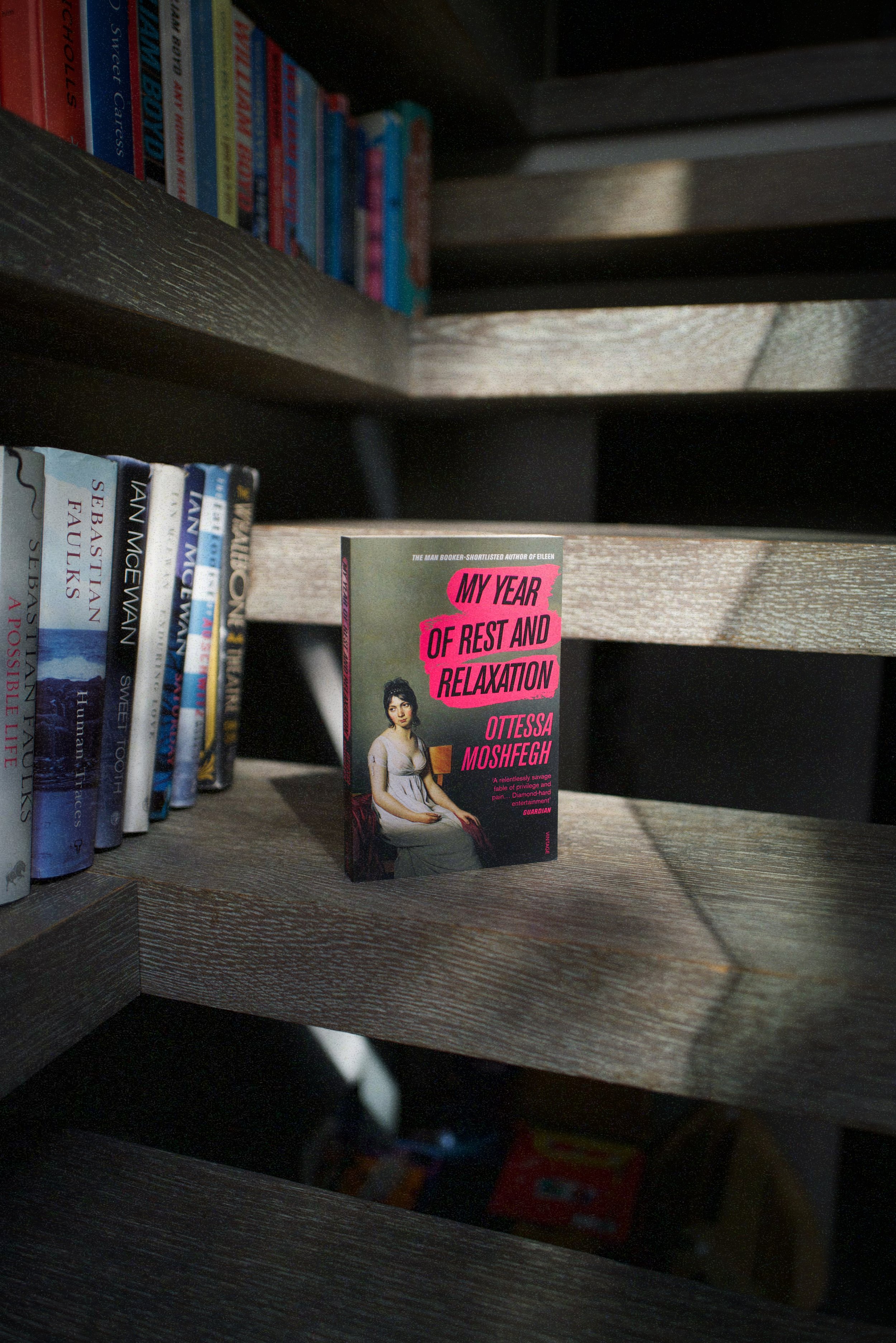

My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh

I’m not a Moshfegh girl I don’t think, friends! And that’s okay! I’ll tell you why I think that is. My favourite books are written from a deep love of life and people. In fact, it’s something I think I look for in all my books, whether I noticed it before now or not. Even in all the brutality depicted in All the Pretty Horses, there are some lovely tender moments between John and his good friend Rawlins. Even in VanderMeer’s weird Finch, there is a sense of kinship between Finch and his colleague Wyte. There is a sense of value in the human community, too. Not to mention my favourites, up there? Gilead, Braiding Sweetgrass and Paradise are full of humanity and beauty. That doesn’t mean there isn’t darkness there, too, but it is balanced. But with Moshfegh? There’s none of that. In fact, I think she writes from a general position of disdain and disgust for humanity. Perhaps there are inklings of hope at the ends of her books, but I think most people agree she’s not known for the most fitting endings. In both Eileen and My Year, they have felt tacked on and awkward. But reading these two books taught me about my reading tastes, and they also taught me I don’t need to prioritise Moshfegh in the future, which are both positive things.

I think I preferred Eileen to this one. I’m sure many of you are familiar with this book. It’s about a woman who takes a bunch of sleeping pills for a year basically and tries to reset her rather miserable existence. There were things to appreciate, I think Moshfegh’s prose is generally smooth, though there are some eye-roll-worthy lines. There is some childhood trauma discussed which explains the main character’s perspective. But I have found with Moshfegh there is a big hole where the real subtext should be. What’s the subtext, women can be gross, too? Considering its subject matter, I would have liked it to engage with the concept of illness and depression a bit more. I don’t know. Not for me!

The New Atlantis by Ursula Le Guin

I got this short story which was published online out from the library and found it to be a perfectly serviceable story about a future world where people’s quality of life is vastly reduced as a result of climate change, and they are closely surveilled for allegiance to the state. It was decent, but not Le Guin’s best work (marriage being illegal was an odd choice). In fact, I think her introduction where she explains why she wrote what she wrote back in the 70s and how things have actually panned out in reality was probably the best bit of this. I read it for completist reasons, and can now rest easy with it ticked off my list.

And that’s it! If I can, I think I need to switch back to monthly versions of this as I’m finally reading more again. Fingers crossed I can squeeze in the time for May.